India’s economic resurgence amidst the turbulence

Fund Manager Q&A - November 2022

What are your thoughts on the high valuations in India?

Vinay: Over the last few years, we have been selling many companies which have become expensive. On the other hand, there are still companies that are attractively valued with robust growth ahead. Our portfolio has an average return on capital employed (ROCE) of over 30% and trades on 20x earnings, which should grow around 15% per year on average.

For example, we had been shareholders in companies like Mphasis or Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) for a long time when Covid hit in 2020. In 2021, when it looked like everything would go digital, revenue visibility for these companies increased and the market extrapolated from it. These companies saved on costs as people stopped travelling, so their margins expanded. Their valuations rose from 15x earnings to 30x - 40x last year.

We were less optimistic, and thought that growth and margins would fall, along with valuations. We sold all our holdings of Mphasis last year and sold most of our position in TCS as well. This year, as these concerns have come to the fore and investors reduced their forecasts, their valuations have become more reasonable and we have started buying again. However, we think the concerns have not played out yet, so we will wait for a better opportunity to buy more.

How are you different from other asset managers?

Vinay: Firstly, when we invest in companies, we are very clear about what we will not do. It is easy to exclude certain practices like tobacco, weapons, gambling, and modern slavery. What is more difficult is assessing who are the people we will not back. For example, we have never invested in two of the largest business groups in India, because of the way they were built and managed, and how they influenced policymaking to their advantage. We will never own them, regardless of how attractive they become in terms of growth or valuations.

The second thing we do differently is that we focus on the people and culture of the businesses we are interested in. We don't build sophisticated spreadsheets in which we try to predict a company's future. Instead, we look at how a company started, who started it, and how it evolved over the cycles - has it been fair to all stakeholders, and what kind of capital allocation decisions were made. We consider how they think about minority shareholders and other stakeholders, and what kind of governance structures they are building. We pay attention to what the board looks like, is there enough independence, is it effective, and whether the family wants it to be effective.

We also pay attention to how the managers are incentivised, their key performance indicators (KPIs), and whether we are aligned over the long term. At many companies, the managers are only incentivised according to revenue or earnings growth. This often comes with acquisitions, increasing leverage and decreasing returns on capital. We think effective KPIs should result in higher return on capital employed (ROCE), and we engage with our companies on this.

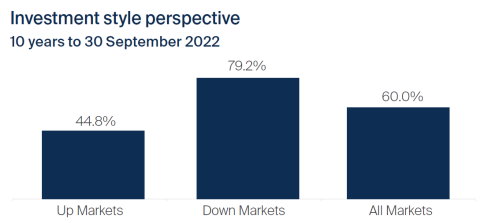

The third aspect which sets us apart is our focus on capital preservation. We have an absolute return mind-set and think of risk in terms of losing money rather than underperforming a benchmark. In our team discussions, we think about the many things that can go wrong. In the 10 years to September 2022, we outperformed the market 45% of the time when markets were up, but in down-markets we performed better around 80% of the time. This preserved capital and created value for our investors over the long term.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The chart represents the monthly outperformance of the strategy for the past 10 years versus the benchmark. All performance data for the FSSA Indian Subcontinent Strategy USD. Source for Fund - Lipper IM / First Sentier Investors (UK) Funds Limited. Performance data is calculated on a gross of fees basis.

Observing leadership changes at India’s largest biscuit company

Vinay: The following examples may help to illustrate the above points. First is Britannia, where we have been shareholders for a long time. We have met this company regularly over the last 20 years, paying attention to the changes in management and whether the governance structures were adequate to protect minority shareholders.

Britannia was established in 1892 and the Wadia family became shareholders in the early 1990s. The Wadia group owns companies in areas like property and airlines - such businesses often require cash and we were concerned that Britannia may have to fund the struggling parts of the group. We also worried about whether the next generation of the Wadia family would return to run the business (usually a negative indicator). When we first looked at Britannia, we thought the board could be stronger.

In 1993, Sunil Alagh was appointed as the company's first professional CEO and the business became very successful. However, he was fired in 2003 and there was no new CEO until 2005. Parle (Britannia's biggest competitor) started gaining market share, while a new competitor, ITC, also launched around this time. At this point, we bought Britannia as valuations had become attractive at under 1x price-to-sales.

Vinita Bali subsequently joined in 2005, bringing deep experience from Coca-Cola and Marico. Feedback from the owner of Marico on Ms Bali’s credentials were very positive, which we thought reassuring. When Varun Berry took over in 2013, he changed the business mix towards more premium products and increased margins.

After all of this and despite changing hands several times, the franchise was still very strong in terms of the brands that Britannia owned. We thought that the industry was attractive and underpenetrated, and Britannia could earn decent returns on capital.

We have continued to meet with the company over the years to engage with the management on key issues. As long-term shareholders, we have put forward our views on its share incentive schemes, board independence and intercorporate deposits (among other topics). The company has since improved in all of these areas.

Improving culture and governance at a leading telecom company

Sree: A second example is Bharti Airtel, one of India's leading telecom companies. We have known the company since the early 2000s and met the management more than 40 times over this period. We saw it become dominant in the domestic market as telecom penetration increased. Throughout this period, we had a number of concerns around the governance as well as the risk appetite of the founder.

This came to the fore when Bharti spent almost USD 11bn on acquiring a large telco in Africa. In a magazine interview at that time, the founder said, “I am like a junkie looking for his next fix.” This was clearly a culture that we would not back.

However, we began to see signs of change around 2016. A new entrant was disrupting India’s telecom industry. Bharti’s promoters realised that the only way to survive was to make significant changes, including to the governance and culture of the company.

Gopal Vittal, a professional CEO from Unilever, was hired and he brought in the governance standards of a multinational company (MNC). In addition, there was a public admission by the founder that the investment in Africa was a mistake. This showed his increasing humility and changing approach in terms of risk appetite and capital allocation. The group subsequently exited a number of unprofitable markets and spun off the Africa subsidiary.

Meanwhile, Singapore Telecommunications (SingTel) had become Bharti’s largest shareholder, with a stake bigger than that of the founding family. We met the CEO of SingTel, who played an increasing role in building guardrails around capital allocation and governance.

Seeing Bharti change for the better with many of our concerns alleviated, we initiated a position in 2017. In the following years, Bharti benefited from industry consolidation as the disruption from new entrant Reliance Jio waned. The company also became more efficient and improved its capital allocation. It is now one of the largest positions in our portfolio.

Engaging on capital allocation discipline at a leading automotive manufacturer

Sree: A third example is Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M), which began as a leading automotive manufacturer and grew into one of the largest conglomerates in India. We have known the company for decades and always held them in high regard for their governance standards. Despite this, we were not shareholders for most of the last seven years because we thought the group's capital allocation discipline was deteriorating. At one point M&M had over 150 subsidiaries, many of which were loss-making and too complicated for us to understand.

We were also shareholders of Mahindra Lifespaces, the real estate arm of the group. The company should have benefited from the shift in demand towards larger, well-reputed developers. But due to internal issues, the company failed to capitalise on these opportunities, which disappointed shareholders.

In 2020 we wrote a letter to the group chairman, Mr Anand Mahindra, highlighting our concerns around the capital allocation of the group and the poor performance of Mahindra Lifespaces. We received a prompt reply in which he acknowledged our concerns and mentioned that the group is setting up a new capital allocation framework. He referred us to Dr Anish Shah, the deputy CEO who was set to take over as group CEO and was driving this change.

When we met Dr Shah earlier this year, we saw significant changes taking place in the company's capital allocation. The group had exited or sold many of their loss-making businesses. More importantly, he announced that the group would exit or sell any subsidiary which did not meet the return on equity (ROE) threshold of 18% within a certain timeframe. We had seen similar changes at other companies like the Tata Group and the great results that had brought for shareholders. We became shareholders in M&M earlier this year.

Meanwhile, at Mahindra Lifespaces, Dr Shah was making the necessary changes for it to reach its potential. Over the last few years, there have been two new CEOs — the first one didn’t work out, but the second CEO was an outsider to the business who then replaced a majority of the senior management team. There has been a significant improvement in the company’s growth profile and profitability since then.

These examples show that if there is a management change which brings more discipline around capital allocation or governance, a re-rating tends to happen.

Source: FSSA Investment Managers, Bloomberg, October 2022.

What is worrying the team at this time?

Vinay: In the medium to long term, the creation of enough job opportunities is a key concern. India's economy has a disproportionately high share in the services sector, and manufacturing needs to expand to raise employment. Otherwise we risk having more social inequality, as India has a young population, many of whom are poor.

Another concern is the increasing concentration of corporate heft. There are two groups in India which seem like they will end up owning everything in India. If that happens, the country will become an oligarchy, which could be a longer-term risk for valuations.

I also worry about the bubble forming in high-quality companies when they decide to enter new categories, as investors tend to reward them with higher valuations based on lofty expectations. This could be an auto component maker wanting to expand into electric cars and car batteries, and trading on 70x price-to-earnings. Or when a pipe manufacturer decides to make paints and adhesives, and starts trading on similar valuations as Asian Paints. One needs to be careful of such businesses.

Sree: Another worry is that in the past, many countries have grown by depleting resources. While India has a lot of growth potential, it has to become more sustainable. For example, we expect car ownership to increase as income levels rise, but many of the most polluted cities in the world are in India. Therefore, companies and the government have to work together towards more sustainable growth.

How far along are Indian companies on the path to sustainability?

Vinay: We do not think there is such thing as a perfect company, there are only shades of grey. We try to help our companies to travel in the right direction. Meanwhile we are also learning and growing in this regard. We have always thought that if a company gets the governance right, and the owners and management care about all of their stakeholders, then even if they are behind on environmental and social factors, they will learn and improve over time. On the other hand, if the governance is lacking, then a company is just greenwashing and making noise.

Sree: We own one cement company which is the Indian subsidiary of Germany’s HeidelbergCement and have engaged with them on worker safety. Their safety track record is far superior compared to peers - the CEO said that a plant manager's incentivisation is affected by even a single injury in the plant, which holds their people accountable. Additionally, Heidelberg? carbon footprint is about 10% lower than its peers in India. When we introduced them to a company that develops carbon capture technologies, that discussion was taken forward by the CEO. We were pleasantly surprised by their willingness to engage, learn and improve.

What excites you about India in the coming 10 to 20 years?

Vinay: I have been investing in India for the last 20 years. Consumer habits are changing, which is quite exciting. For example, in the early years, there was a case for increasing penetration in basic consumer staples like soaps, shampoos and laundry detergents. Companies like Unilever were the obvious beneficiaries as market leaders. Today many of these categories are well penetrated and a higher share of consumer budgets are moving towards discretionary products. Indians are buying new vehicles and homes and everything that goes with it, like pipes or construction chemicals.

Similarly for financial businesses, the industry was underpenetrated 20 years ago. The incumbent state-owned banks were dominant with over 80% market share. Well-run private banks like HDFC Bank gradually gained market share and state-owned banks's share fell to 60%. As basic deposit accounts have become more common, in the coming 10 to 20 years we expect more demand for insurance and wealth management products. We own companies which should benefit from this, like CAMS, a registrar and transfer agent (RTA) for mutual fund companies, or ICICI Lombard, a general insurance business.

Sree: We are also excited by the large opportunity set of businesses that are small but will become large over time. An example is Blue Star, one of the leading domestic air conditioner companies. This is a high-quality, well-governed company with high returns on capital. India has an air conditioner penetration rate of 5% and there are a few million units sold each year. This compares with several tens of millions of ACs sold in other markets in the region, where penetration can reach 70%. We think this business could become several times its current size. It is a large business of the future, hiding in a small market capitalisation currently.

Company data retrieved from company annual reports or other such investor reports. Financial metrics and valuations are from FactSet and Bloomberg. As at 31 October 2022 or otherwise noted.

Important Information

The information contained within this material is generic in nature and does not contain or constitute investment or investment product advice. The information has been obtained from sources that First Sentier Investors (“FSI”) believes to be reliable and accurate at the time of issue but no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the fairness, accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information. To the extent permitted by law, neither FSI, nor any of its associates, nor any director, officer or employee accepts any liability whatsoever for any loss arising directly or indirectly from any use of this material.

This material has been prepared for general information purpose. It does not purport to be comprehensive or to render special advice. The views expressed herein are the views of the writer at the time of issue and not necessarily views of FSI. Such views may change over time. This is not an offer document, and does not constitute an investment recommendation. No person should rely on the content and/or act on the basis of any matter contained in this material without obtaining specific professional advice. The information in this material may not be reproduced in whole or in part or circulated without the prior consent of FSI. This material shall only be used and/or received in accordance with the applicable laws in the relevant jurisdiction.

Reference to specific securities (if any) is included for the purpose of illustration only and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell the same. All securities mentioned herein may or may not form part of the holdings of First Sentier Investors' or FSSA Investment Managers??portfolios at a certain point in time, and the holdings may change over time.

In Hong Kong, this material is issued by First Sentier Investors (Hong Kong) Limited and has not been reviewed by the Securities & Futures Commission in Hong Kong. In Singapore, this material is issued by First Sentier Investors (Singapore) whose company registration number is 196900420D. This advertisement or material has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

First Sentier Investors and FSSA Investment Managers are business names of First Sentier Investors (Hong Kong) Limited. First Sentier Investors (registration number 53236800B) and FSSA Investment Managers (registration number 53314080C) are business divisions of First Sentier Investors (Singapore).

First Sentier Investors (Hong Kong) Limited and First Sentier Investors (Singapore) are part of the investment management business of First Sentier Investors, which is ultimately owned by Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. (“MUFG”), a global financial group. First Sentier Investors includes a number of entities in different jurisdictions.

MUFG and its subsidiaries are not responsible for any statement or information contained in this material. Neither MUFG nor any of its subsidiaries guarantee the performance of any investment or entity referred to in this material or the repayment of capital. Any investments referred to are not deposits or other liabilities of MUFG or its subsidiaries, and are subject to investment risk, including loss of income and capital invested.